This irregular “Dharma Questions” series deals with “Dharma” meaning both the truth of the nature of reality and some Buddhist teachings. Please see this post on the intensions for questioning and not questioning. Amongst other things these questions can be:

- thought experiments

- borderline musings not meant to be answered

- from lack of effort of not contemplating or researching them yet

- How is the rate of annica (aka inconstancy/impermanence) determined? How does annica work?

- Is metta still dukkha?

- Are parasites (sentient) beings?

- Would constantly contemplating (the existence of) sentient beings aid in amplifying sentient beings’ continual wandering in Samsara, or the opposite where not considering sentient beings enough aids in giving rise to continued existence of sentient beings (in order to be valued, honored, and respected)? Or both of these scenarios, or neither, or something else, or what significant effects do paying attention to, or not paying attention to sentient beings have?

- Would samsara exist without beings?

- What if one was offered — or could access a route to — expedited Buddhahood with incalculable benefits to/for all beings everywhere, but doing so would activate and increase atrocities of Mara’s armies (and the like) upon humanity, at least in the short term? (What would you choose?)

- Why is it called the form realm? Don’t beings in the sense desire realm experience forms regularly?

- Why aren’t the three characteristics of existence more easily, continuously, and readily apparent?

- Do non-dual teachings bypass (the teaching/learning mechanism) of polarity? Isn’t polarity to be mastered? (If not,) how and why did polarity come about?

- Seems like there’s so much weight put on the last mind moment but I feel what’s often left out is so much has led up to condition and cause that last mind moment. If this is not pointed out then there seems like there could be a hell of lot of pressure on the last mind moment. What perceptions are skillful and wise about the last mind moment?

- Does chanting “Amitābha” when a thought arises to counteract and quiet the mind discourage investigation, contemplation and independent thinking?

- If each Buddha has an associated pure land why is there so much emphasis on Amitābha Buddha?

- What karmic effect/consequences, if any, are there for an intentionally willful action to balance and/or eliminate/cease karma?

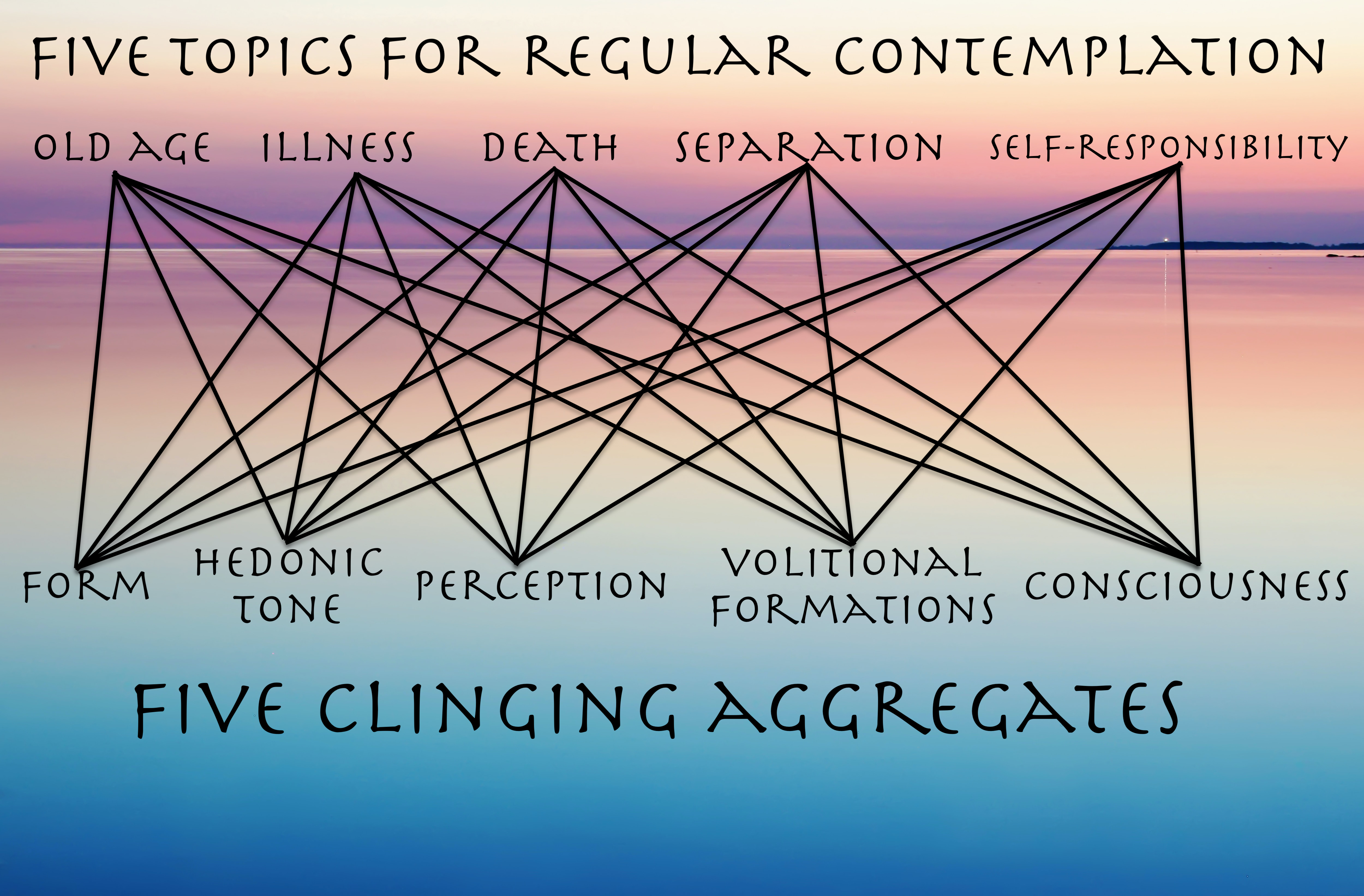

- Does it make sense to apply the five daily reflections to each of the five aggregates?

- What is the reasoning for (the difference between) six and 10 paramitas in Theravada and Mahayana respectively?

- Can too much emphasis on emptiness lead away from more life preserving and/or life promoting choices?

- Can merit be hijacked (and held ransom/hostage)?

- How is (equal) merit transfer distributed (without hijacking)?

- How do (Christian and other traditions’) angelic hierarchies compare with the Buddhist cosmology of heavenly realms? [check Ajahn Puddhadammo’s book on Buddhist cosmology: THE BUDDHIST COSMOS: A Comprehensive Survey of the Early Buddhist Worldview; according to Theravāda and Sarvsātivāda sources]

- Do these lines in the Metta Sutta mean action should be taken? ‘Let none deceive another or despise any being in any state. Let none through anger or ill-will wish harm upon another.’ If so, to what extent ought one act to prevent and address harm, deception and despising?

- Can one of the 4 elements be isolated and exist without another? If not, why not? If so, how? And would it (then) be considered a non-compounded, permanent thing? Rephrased: Are each of the individual four elements (non)compounded, (im)permanent things?

- What is the root (causes and) condition of (each of the four) element(s)?

August 13, 2023 Update: What easier way to get “answers” these days than to ask ChatGPT. Still very glad to be human. So here’s some of those mostly subpar answers:

2) In Buddhism, metta refers to loving-kindness or benevolence towards all beings. Dukkha, on the other hand, is the concept of suffering or unsatisfactoriness that is inherent in life.

Metta itself is not considered dukkha. In fact, metta is seen as a way to alleviate dukkha and cultivate a sense of well-being and happiness. By cultivating loving-kindness towards oneself and others, one can reduce suffering and promote harmony.

However, it’s important to note that even with metta practice, one may still experience dukkha due to the impermanent nature of existence and the various causes and conditions that give rise to suffering. Metta can help individuals develop resilience and compassion in the face of dukkha, but it does not eliminate it entirely.

Ultimately, the goal in Buddhism is to transcend dukkha through enlightenment or awakening. While metta can be a helpful practice on this path, it is not the ultimate solution to completely eradicate dukkha.

5) No, samsara would not exist without beings. Samsara is a concept in Buddhism and Hinduism that refers to the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. It is believed that beings are trapped in this cycle due to their desires and attachments. Without beings to experience this cycle, samsara would not have any meaning or existence.

7) The term “form realm” in Buddhism refers to a specific realm of existence within the Buddhist cosmology. It is one of the higher realms, above the sense desire realm and below the formless realm.

In the form realm, beings experience existence primarily through subtle forms or bodies, rather than through gross physical senses as in the sense desire realm. These subtle forms are said to be more refined and less subject to suffering compared to the physical bodies experienced in the sense desire realm.

While it is true that beings in the sense desire realm also experience forms regularly, their experience is primarily based on sensory perceptions and desires associated with physical senses. In contrast, beings in the form realm have transcended these sensory desires and rely on more refined forms of perception.

The term “form realm” is used to distinguish this specific level of existence from others within Buddhist cosmology, highlighting its unique characteristics and qualities.

8) The three characteristics of existence in Buddhism refer to impermanence (anicca), suffering (dukkha), and non-self (anatta). These characteristics are not easily, continuously, and readily apparent for several reasons:

- Ignorance: One of the main reasons is ignorance or lack of awareness. Most people are not fully aware of the true nature of reality and are caught up in their own perceptions and beliefs. They cling to the idea of permanence, seek pleasure, and identify with a fixed sense of self. This ignorance prevents them from seeing the impermanent, unsatisfactory, and non-self nature of existence.

- Attachment and aversion: Human beings tend to attach themselves to pleasant experiences and try to avoid unpleasant ones. This attachment and aversion create a biased perception of reality, where they only focus on what they desire or fear. This selective attention hinders them from seeing the broader picture of impermanence, suffering, and non-self.

- Delusion: Delusion refers to the distorted perception or misunderstanding of reality. People often have misconceptions about the true nature of existence due to cultural conditioning, personal biases, or limited knowledge. These delusions cloud their understanding and prevent them from recognizing the three characteristics.

- Subtlety: The three characteristics are not immediately obvious because they operate at a subtle level that requires deep insight and contemplation to understand fully. Impermanence can be observed in some obvious changes like aging or seasons but is harder to perceive in more subtle phenomena like thoughts or emotions. Similarly, suffering may not be apparent when one is experiencing temporary pleasure or distraction. Non-self is even more challenging as it challenges deeply ingrained beliefs about an inherent identity.

- Lack of mindfulness: Mindfulness plays a crucial role in recognizing the three characteristics as it involves being fully present in each moment without judgment or attachment. However, most people live their lives on autopilot, lost in thoughts, worries, or distractions. This lack of mindfulness prevents them from observing the ever-changing nature of reality and understanding the three characteristics.

Overall, the lack of awareness, attachment, aversion, delusion, subtlety of these characteristics, and the absence of mindfulness contribute to their difficulty in being easily, continuously, and readily apparent to most individuals.

9) Non-dual teachings do not necessarily bypass the teaching/learning mechanism of polarity, but they offer a different perspective on it. Polarity refers to the concept of opposites or dualities, such as good and bad, light and dark, pleasure and pain. In non-dual teachings, the emphasis is on recognizing the underlying unity that transcends these apparent opposites.

While polarity can be seen as something to be mastered in certain spiritual traditions or personal development paths, non-dual teachings suggest that true liberation lies in transcending the identification with polarity altogether. They invite individuals to move beyond the limited perspective of right and wrong, good and bad, and instead recognize the inherent wholeness and interconnectedness of all things.

The question of how and why polarity came about is a complex one with various philosophical interpretations. Some spiritual traditions suggest that polarity arises from a fundamental illusion or ignorance about our true nature. This illusion creates a sense of separation and gives rise to dualistic thinking. From this perspective, polarity is seen as a product of our conditioned minds.

Others may view polarity as an inherent aspect of existence itself. They see it as a necessary part of the play or dance of life, where contrasting experiences provide opportunities for growth, learning, and self-realization. In this view, polarity is not something to be overcome or mastered but rather embraced as an integral part of the human experience.

Ultimately, whether one seeks to master polarity or transcend it depends on their individual spiritual path and understanding. Non-dual teachings offer an alternative perspective that invites individuals to go beyond polarized thinking and discover a deeper truth that unifies all apparent opposites.

12) There are several reasons why there is a significant emphasis on Amitābha Buddha and his associated pure land, known as Sukhavati or the Pure Land of Ultimate Bliss, in certain Buddhist traditions:

- Accessibility and inclusivity: Amitābha Buddha’s pure land is believed to be easily accessible to all beings, regardless of their spiritual level or past actions. It is considered a place of refuge for those seeking liberation from suffering. This inclusivity makes it particularly appealing to many practitioners.

- Pure Land teachings: The Pure Land teachings emphasize the practice of mindfulness and recitation of Amitābha Buddha’s name (known as nianfo or nembutsu) as a means to attain rebirth in Sukhavati. This practice is seen as a simple and effective method for ordinary individuals to cultivate faith, devotion, and concentration.

- Compassion and salvation: Amitābha Buddha is revered for his boundless compassion and vow to save all sentient beings from suffering. His pure land is seen as a manifestation of this compassionate vow, providing an ideal environment for spiritual growth and enlightenment.

- Cultural influence: The emphasis on Amitābha Buddha and the Pure Land teachings has been particularly strong in East Asian Buddhist cultures such as China, Japan, and Korea. This cultural influence has contributed to the popularity and widespread practice of Pure Land Buddhism in these regions.

- Hope for afterlife: The concept of rebirth in Sukhavati offers hope for a favorable afterlife where one can continue their spiritual journey towards enlightenment under the guidance of Amitābha Buddha.

It’s important to note that while there may be an emphasis on Amitābha Buddha in certain traditions, other Buddhas and their associated pure lands are also revered by different Buddhist schools or individuals based on their personal inclinations or practices. Ultimately, the choice of which Buddha or pure land to focus on depends on the individual’s spiritual affinity and personal beliefs.

13) In many spiritual belief systems, the concept of karma refers to the law of cause and effect, where one’s actions in the past, present, or future have consequences that affect their future experiences. The idea of intentionally balancing or eliminating karma is often seen as an attempt to mitigate negative consequences or create positive outcomes. However, it is important to note that the understanding and interpretation of karma can vary across different philosophies and religions.

According to some beliefs, intentionally taking actions to balance or eliminate negative karma can have positive effects on one’s life. These actions may include acts of kindness, self-reflection, seeking forgiveness from others, making amends for past wrongdoings, practicing meditation or mindfulness, and cultivating virtues such as compassion and generosity.

By consciously choosing positive actions and intentions, individuals may be able to create a more harmonious and balanced karmic cycle. This can lead to experiencing more favorable circumstances in the future and potentially reducing the impact of negative karmic consequences.

However, it is important to approach the concept of karma with a balanced perspective. Some belief systems also emphasize that karma cannot be completely eliminated or ceased through intentional actions alone. They argue that every action has consequences that ripple through time and space, creating a complex web of interconnectedness. Therefore, while intentional actions can influence one’s karmic trajectory positively, they may not completely erase all past negative karmic effects.

Ultimately, the understanding of karma and its consequences varies among different spiritual traditions. It is advisable to explore these concepts within the context of your own beliefs or consult with spiritual teachers or practitioners who specialize in your specific tradition for a more comprehensive understanding.

19) Christian and other religious traditions’ angelic hierarchies differ significantly from the Buddhist cosmology of heavenly realms. Here are some key differences:

- Existence of God: Christian and other traditions believe in the existence of a supreme being, such as God, who governs the angelic hierarchy. In contrast, Buddhism does not recognize a creator god or a supreme being.

- Purpose and Nature: Angels in Christian traditions are seen as divine messengers and servants of God, created to carry out specific tasks and protect humans. They are considered to be spiritual beings with distinct personalities and individual identities. In Buddhism, heavenly beings (devas) are not necessarily messengers or servants but rather inhabitants of higher realms who enjoy greater happiness due to their past good deeds.

- Hierarchy: Christian angelic hierarchies often depict multiple levels or orders of angels, each with different roles and responsibilities. These hierarchies are based on scriptural interpretations and theological teachings. In Buddhism, the heavenly realms consist of various levels known as “Deva Realms,” which include different types of devas based on their level of spiritual attainment.

- Rebirth: According to Christian beliefs, angels do not experience rebirth or reincarnation but exist eternally in their respective hierarchical positions. In Buddhism, devas are subject to the cycle of rebirth like all other sentient beings, including humans.

- Ultimate Goal: In Christianity and other traditions, the ultimate goal is often salvation or union with God through faith and righteous living. The angelic hierarchy plays a role in this process by guiding humans towards this goal. In Buddhism, the ultimate goal is liberation from the cycle of birth and death (samsara) through enlightenment (nirvana), which transcends all heavenly realms.

It’s important to note that these comparisons provide a general overview and may vary within different denominations or schools within each tradition. Additionally, interpretations and beliefs can differ among individuals within the same tradition.

21) According to classical philosophy and ancient beliefs, the four elements (earth, water, air, and fire) are considered to be interdependent and cannot exist in isolation from one another. This concept is based on the idea that these elements are fundamental building blocks of the physical world.

The interdependence of the elements can be understood through their interactions. For example, fire requires air to burn, while air needs space (often associated with the element of ether) to exist. Water is necessary for earth to be fertile and support life. These relationships suggest that each element relies on others for its existence or expression.

Therefore, it is generally believed that isolating one element completely from the others would disrupt this balance and result in an incomplete or unsustainable state. In this sense, the individual elements are considered compounded rather than non-compounded.

Additionally, in terms of permanence, classical philosophy views all physical phenomena as impermanent and subject to change. The four elements are seen as part of this impermanent nature of reality.

It’s important to note that these concepts are rooted in ancient philosophical frameworks and may not align with modern scientific understanding.

22) The root condition of each of the four elements can be explained as follows:

- Earth: The root cause or condition of the earth element is stability and solidity. It represents the physical aspect of things, including the ground, mountains, and all solid matter. The earth element is associated with qualities like groundedness, reliability, and endurance.

- Water: The root cause or condition of the water element is fluidity and adaptability. Water represents the flow and change in life. It symbolizes emotions, intuition, and purification. The water element is associated with qualities like flexibility, empathy, and healing.

- Fire: The root cause or condition of the fire element is heat and transformation. Fire represents energy, passion, and creativity. It symbolizes both destruction and creation. The fire element is associated with qualities like enthusiasm, courage, and inspiration.

- Air: The root cause or condition of the air element is movement and expansion. Air represents freedom, communication, and intellectuality. It symbolizes thoughts, ideas, and mental processes. The air element is associated with qualities like curiosity, adaptability, and clarity.

These elements are not only physical substances but also metaphors for understanding different aspects of life’s experiences and characteristics within various belief systems such as Hinduism or Buddhism.